Worked assiduously to secure release of Indian fishermen from Bangladesh: MEA

Earlier on Thursday, 95 Indian fishermen were handed over by Bangladesh authorities to the Bangladesh Coast Guard for handing over to the Indian Coast Guard on January 5.

News headlines from Bangladesh, and the diverse reactions in India and other countries, are not only disturbing and distressing, but also disquieting as they bode ill for developments in South-east Asian politics.

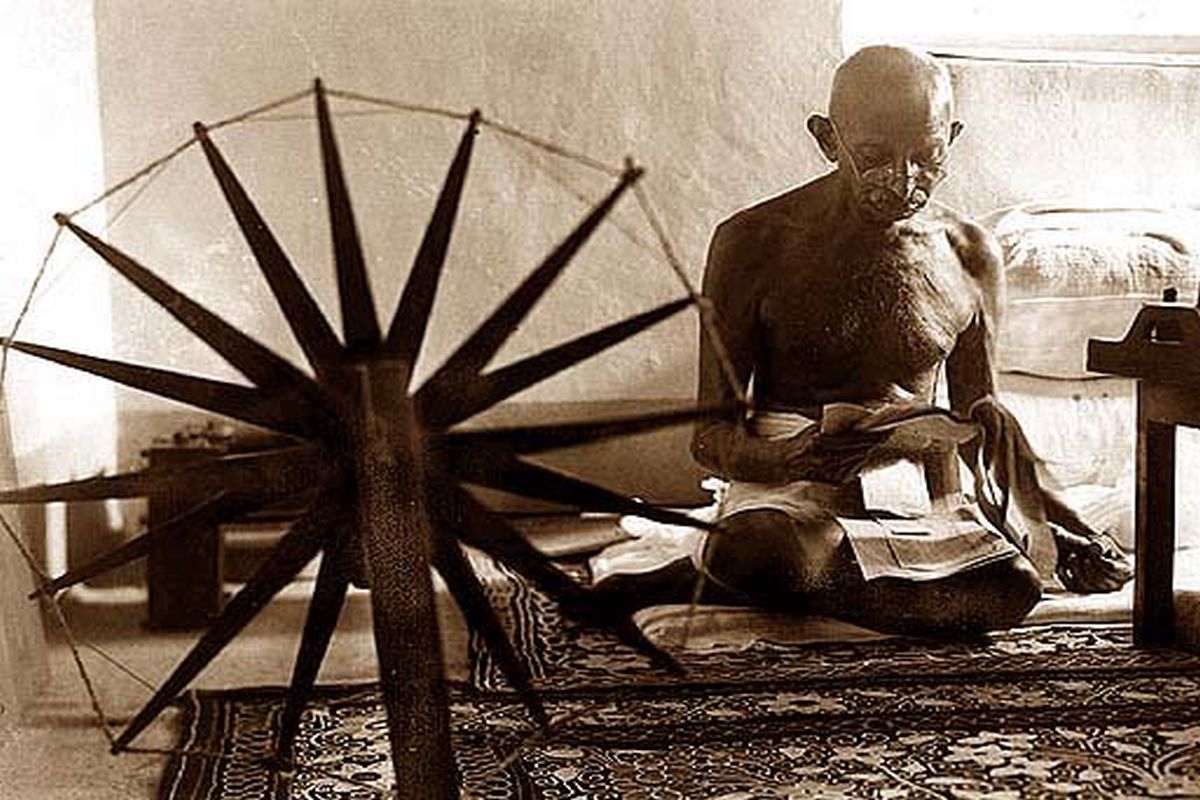

(Image: Facebook/@Mahatma-Gandhi)

News headlines from Bangladesh, and the diverse reactions in India and other countries, are not only disturbing and distressing, but also disquieting as they bode ill for developments in South-east Asian politics. The promising dawn of the ‘century of Asia’ seems to be eclipsed in the dark shadows of violence. Bangladesh, liberated in 1971 with the help of the Indian Army, is at the crossroads of history facing the harsh realities of civilian-Army politics, ethnic clashes, bloodshed and social turmoil across its otherwise serene riverine countryside.

In the new year of 2025, it pays to recall the subcontinent’s historic Swadeshi movement and the heights it reached in 1905: also, an opportune moment to pay homage to heroes of the movement, 120 years after their singular and often spectacular achievements. It is also an eyeopener to the shaping of nationalist thought and action which brought together some of the finest, bravest, boldest Indians when the decision to partition Bengal was implemented by the British Raj in 1905. The unity demonstrated in 1905 could serve as a lesson of history today. Years before Prof Sumit Sarkar of Delhi University wrote the epic ‘The Swadeshi Movement in Bengal 1903-1908’, his address during the Indian History Congress in 1970 sought a deeper understanding of the nature and working of imperialism, both in India and on a world scale.

Advertisement

His address was titled ‘Imperialism and Nationalist Thought’; it was focused on Bengal while acknowledging equally significant political and social developments in Maharashtra and Punjab. The Swadeshi movement had gained momentum ostensibly as a reaction to what seemed as a territorial reorganization of the Bengal Presidency. The undivided province had an area of 189,000 square miles and a population (in 1901) of 78.50 million. The plan of the British Raj was to separate the largely Muslim areas of the eastern areas from the predominantly Hindu areas in the west.

Advertisement

Lord Curzon, then the Viceroy of India, forged this imperial plan to make West Bengal for Hindus and East Bengal for Muslims. What it triggered was an upsurge of different movements against the British Raj: Swadeshi had multiple strands, different voices and diverse trajectories all adding up to anti-colonial, anti-imperial struggles which took the British Raj by surprise. Prof Sarkar pointed out, “Continuities at first sight seem more noticeable than breaks when we look at Swadeshi Bengal from the ‘moderate nationalism’ point of view, and more specifically its political aspects which had crystallized around concrete grievances like government jobs and Council seats, issues directly affecting only a handful…Partition was an affront to the growing sense of unity among the Bengali-speaking people, a sense by no means all pervasive but still certainly affecting many others besides zamindars, Calcutta lawyers or Congress politicians; the highhanded redrawing of maps by foreigners without any consultation with the inhabitants was resented as a peculiar gross kind of white arrogance and racial discrimination was the theme which could unite the proudest zamindar or ‘bhadralok’ with the meanest of plebians.”

The professor referred to a spectrum of Indian newspapers continually focusing on cases of assault and judicial partiality, and the depth of bitterness amongst the people. The original Risley Scheme, explained Prof Sarkar, would lead to the transferred East Bengal districts getting submerged in ‘backward’ Assam and losing several privileges including its Legislative Council and a Board of Revenue; the enlarged Partition plan would restrict employment opportunities for its people, reduce educational facilities by cutting off Calcutta from East Bengal. It would also curtail the jurisdiction of the Calcutta High Court, at the same time upsetting the Permanent Settlement as the new province of East Bengal would require new taxes. Civil servants like H H Risley had convinced themselves that the whole Swadeshi movement was being engineered by interest groups led by the ‘bhadralok’, and were consequently supremely confident that “the native will quickly become accustomed to the new conditions”.

“Bengal united is a power; Bengal divided will pull in several different ways. That is perfectly true and is one of the merits of the scheme,” wrote Risley in one of his notes on 6 December 1904. “The only rejoinder that I can think of is that Bengal is very densely populated; that Eastern Bengal is the most populated portion, that it needs rooms for expansion and that it can only expand towards the East. So far from hindering national development we are really giving it greater scope, and enabling Bengal to absorb Assam,” wrote the civil servant who had contributed immensely to ethnographic studies on India. These words, often quoted in different contexts, attained a degree of notoriety. What spurred Lord Curzon on was pretty obviously a political motive. Prof Sarkar quoted letters and notes from the Curzon papers, “The Bengalis, who like to think themselves a nation, and who dream of a future when the English will have been turned out and a Bengali Babu will be installed in Government House, Calcutta, of course bitterly resent any disruption that will be likely to interfere with the realization of this dream.

If we are weak enough to yield to their clamour now, we shall not be able to dismember or reduce Bengal again; and you will be cementing and solidifying, on the eastern flank of India, a force already formidable, and certain to be a source of increasing trouble in the future.” Lord Minto’s memorandum dated 5 February 1906 was equally significant to note when he observed: “Yet partition should and must be maintained, since the diminution of the power of the Bengali political agitation will assist to remove a serious cause for anxiety…It is the growing power of a population with great intellectual gifts and a talent for making itself heard, a population which, though it is very far from representing the more manly characteristics of the many races of India, is not unlikely to influence public opinion at home most mischievously.

Therefore, from a political point of view alone, putting aside the administrative difficulties of the old province, I believe partition to have been very necessary…” Minto’s notes and memos are not merely part of India’s administrative history but have added immensely to the social-cultural identity of the Bengalis, then and now. In the context of current political turmoil, it is often overlooked that these eastern parts of India’s subcontinent have historical legacies that stretch back centuries. The entire Bengal region during the thousand years preceding the British conquest had enjoyed long periods of autonomy and unity centred successively around Gaur, Dacca and Murshidabad. The social historian in Prof Sarkar has shown how the memories of such feudal independence and the undoubted facts of linguistic and literary unity, led to the emergence of something like a common culture at the village level based on an amalgam of Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim and primitive folk elements.

“On this came to be superimposed the more obvious unity of the English-educated bhadralok and its greatest creation ~ the nineteenth-century Bengali literature. Calcutta had become the real metropolis for the whole of Bengal, attracting students from all districts, sending out its graduates to teach in mufassil colleges and far-flung village schools, serving as the apex of the whole legal system and profession, and functioning also as the centre of trade by railway, river and ocean. Districts like Dacca, Barisal, Comilla or Mymensingh responded eagerly to impulses of social reform or political activity originating in Calcutta,” wrote Prof Sarkar in ‘The Swadeshi Movement in Bengal’ for the benefit of those attempting to comprehend the complexity of India’s socio-cultural ethos. The sense of unity demonstrated by Bengali-speaking people during the Swadeshi movement from 1903 to 1908 clearly could not be reduced to merely a few decades of political activities. With 1905 being the watershed year for the Swadeshi movement, Prof Sarkar identified five strands in what was clearly categorized as ‘economic swa deshi’:

1) organisation of technical education and industrial research;

2) promotion of swadeshi sales through exhibitions, shops and cost-price hawking by volunteers;

3) fostering and revival of traditional indigenous crafts;

4) starting of new industries based on modern techniques, and

5) floating of swadeshi banks, insurance companies and inland shipping concerns. The spirit of Swadeshi was soon manifested through economic activities with a patriotic component: Kishorilal Mukherji’s Sibpur Iron Works and Prafullachandra Ray’s Bengal Chemicals showed the way. The popularity of their enterprises made the Swadeshi movement present a panacea for all the ills of India: industrial devastation, economic drain and growing unemployment. In fact, Ray explained the motives behind setting up of Bengal Chemicals: “Our educated young men, the moment they came out of their colleges, were on the look out for a situation or a soft job under the Government, or failing that in a European mercantile firm.

The professions were becoming overcrowded. A few came out of the Engineering College, but they were helpless seekers after jobs…What to do with all these young men? How to bring bread to the mouths of the ill-fed, famished young men of the middle classes?” Despite the passage of 120 years, the basic causes of social-political unrest and turmoil in the subcontinent remain quite the same.

(The writer is a researcher author on history and heritage issues and a former deputy curator of Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya)

Advertisement